The biggest lie ever told about Africa? That it’s poor.

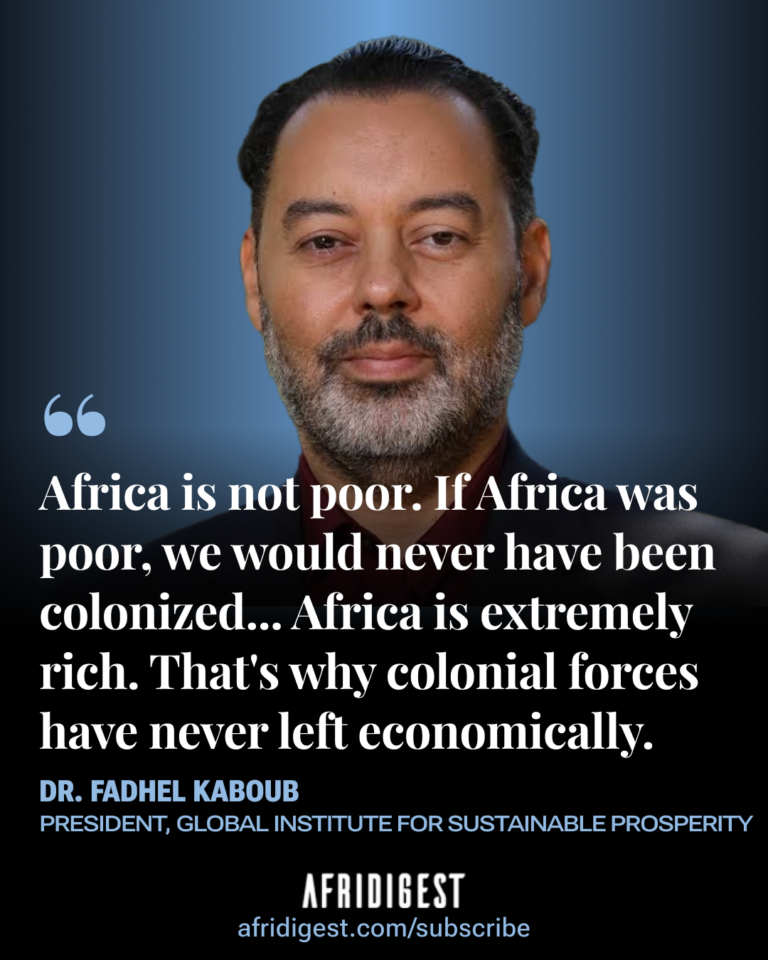

“Africa is not poor. If Africa was poor, we would never have been colonized… Africa is extremely rich. That’s precisely why colonial forces have never left economically.”

That’s Tunisian economist Dr. Fadhel Kaboub, President of the Global Institute for Sustainable Prosperity, challenging a fundamental narrative about the continent.

According to Kaboub, Africa’s perceived “poverty” is a feature, not a bug, of the global economic system.

“Nobody would ever set foot here to extract anything [if we were actually poor],” he explains.

His argument?

Africa remains deliberately trapped in systems designed to maintain colonial economic relationships.

The evidence? Three structural traps that perpetuate dependency:

- Food deficits: Africa imports 85% of its food despite being a former “breadbasket” — a result of colonial agricultural policies that pushed countries toward cash crops for export instead of food sovereignty

- Energy deficits: Even major oil producing countries like Nigeria have had to import refined fuels, while the continent’s massive renewable energy potential remains largely untapped due to limited access to manufacturing technology

- Manufacturing deficits: African countries are locked into producing low value-added goods at the bottom of global value chains, while importing high value-added components and technology

“We consume what we don’t produce and produce what we don’t consume,” Kaboub emphasizes.

The result of those deficits?

Perpetual trade imbalances that weaken currencies, import inflation, and ultimately trap countries in cycles of debt and dependency — forcing governments to prioritize debt servicing over development.

But Kaboub sees a path forward through what he calls “The geopolitical bargain of the century” — African nations negotiating as one with global powers to reposition Africa at the center of a new international economic order.

“All African countries are in the same traps, and it’s much easier to co-design a pan-African strategy to get out of those traps collectively,” he argues.

His vision?

A unified Africa using its vast resource wealth (particularly in critical minerals), market size, and young workforce as leverage to force technology transfer and build true economic sovereignty.

The alternative is remaining locked in extractive relationships disguised as “partnerships” and “development aid” in Kaboub’s view.

“No new multipolar world can be born without the African continent and the rest of the Global South being repositioned from the bottom of the hierarchy,” he insists.

What’s your take on Kaboub’s analysis?

✦ Do you agree that Africa’s “poverty” is manufactured, and that colonial structures still drive economic extraction today?

✦ Is pan-African integration realistic given current political realities, or are the structural barriers that are too difficult to overcome?

✦ How can African countries balance the need for immediate development financing with the goal of long-term economic sovereignty — or is this a false choice?

Join the conversation on LinkedIn.

Buy the book from Dr. Kaboub here.

Share: