Here are five lessons founders and builders can learn from MNT-Halan’s story:

- Serve underserved markets that have lower levels of competition.

The major components of MNT-Halan today — Mashroey, Tasaheel, Raseedy, and Halan — were all pioneers in their respective verticals and gained ground by offering unique value in the marketplace. - Get support from larger organizations that can accelerate your growth.

Early on in their journey, MNT-Halan’s main constituent companies leveraged capabilities and assets of GB Auto, a publicly traded automotive market leader. - Maintain a sober view of reality — kill what’s not working & double down on what is.

While its ride-hailing operations experienced a lot of initial traction, MNT-Halan shuttered the effort and doubled down on lending as a growth lever with positive unit economics. - Embrace serendipity and say yes to new opportunities.

MNT-Halan’s founder Mounir Nakhla repeatedly said yes where others might have said no. He agreed to launch Mashroey and Tasaheel as subsidiaries of GB Auto in which he held just a small minority share, he agreed to launch a new tech-focused Halan venture instead of simply riding out his previous microfinance successes, and he agreed to the formation of MNT and the acquisition of Halan. - Play long-term games and guard your reputation.

Many of the opportunities that came Nakhla’s way came as a result of his reputation. He was approached to launch Mashroey, trusted to co-found Tasaheel, and sought out regarding Halan. Burnishing your reputation by executing competently pays dividends over the long run.

In 331 BC, Alexander the Great, then the most powerful man in the known world, paid a visit to the Oracle of Amun Ra in Egypt.

The oracle, located at Siwa, a desert oasis roughly 350 miles west of Cairo, was said to have confirmed him not only as the legitimate Pharaoh of Egypt, but also as a descendant of the gods.

Alexander the Great kneeling before the High Priest of Ammon, by Francesco Salviati, c. 1530-1535. The British Museum.

Alexander III of Macedon thus became an Egyptian unicorn in a sense: he was a foreigner pronounced son of Amun, chief god of the Egyptian pantheon.

Two Mounirs in Siwa

More than two thousand years later, in 1996 or thereabout, Cairo-based Egyptian businessman Mounir Neamatalla made his own pilgrimage 500km west of the Nile to the Siwa oasis.

Mounir Neamatalla, PhD. Source: NOW Transforming Hospitality.

Fifteen years or so earlier, he had founded Environmental Quality International (EQI), a renowned consulting firm focused on sustainable development & microfinance, and was now in search of new opportunities.

Taking in Siwa’s lush palm groves, majestic rock formations, and sparkling salt lakes, he decided to put his sustainable development theories into practice at the oasis.

He went on to purchase over 70 acres of land from the Egyptian government and established a number of environmentally friendly ‘eco-lodges,’ including the Adrère Amellal — a property whose name (“White Mountain” in Berber) refers to the massive limestone cliff that towers over it.

The Adrère Amellal ecolodge.

Neamatalla’s nephew, Mounir Nakhla, joined EQI in 2000 after completing his studies in London. As an EQI board member, and later as managing partner of the firm, he developed an appreciation for businesses with low levels of competition, low fixed costs that facilitated profitability, and an outsized positive impact on local communities.

Here’s what the two Mounirs told a Wharton business journal at the time:

Those themes — serving underserved communities, identifying and exploiting opportunities ahead of the competition, and prioritizing profitability — would follow the younger Mounir throughout his professional journey.

The Mashro’ey project

By 2009, there was another opportunity that would prove irresistible to Mounir Nakhla.

Tuk-tuks, three-wheeled motorized rickshaws, which were virtually nonexistent in the country when he joined EQI almost a decade earlier, had become commonplace on Egyptian streets as urban and peri-urban taxis.

Source: EgyptianStreets.com

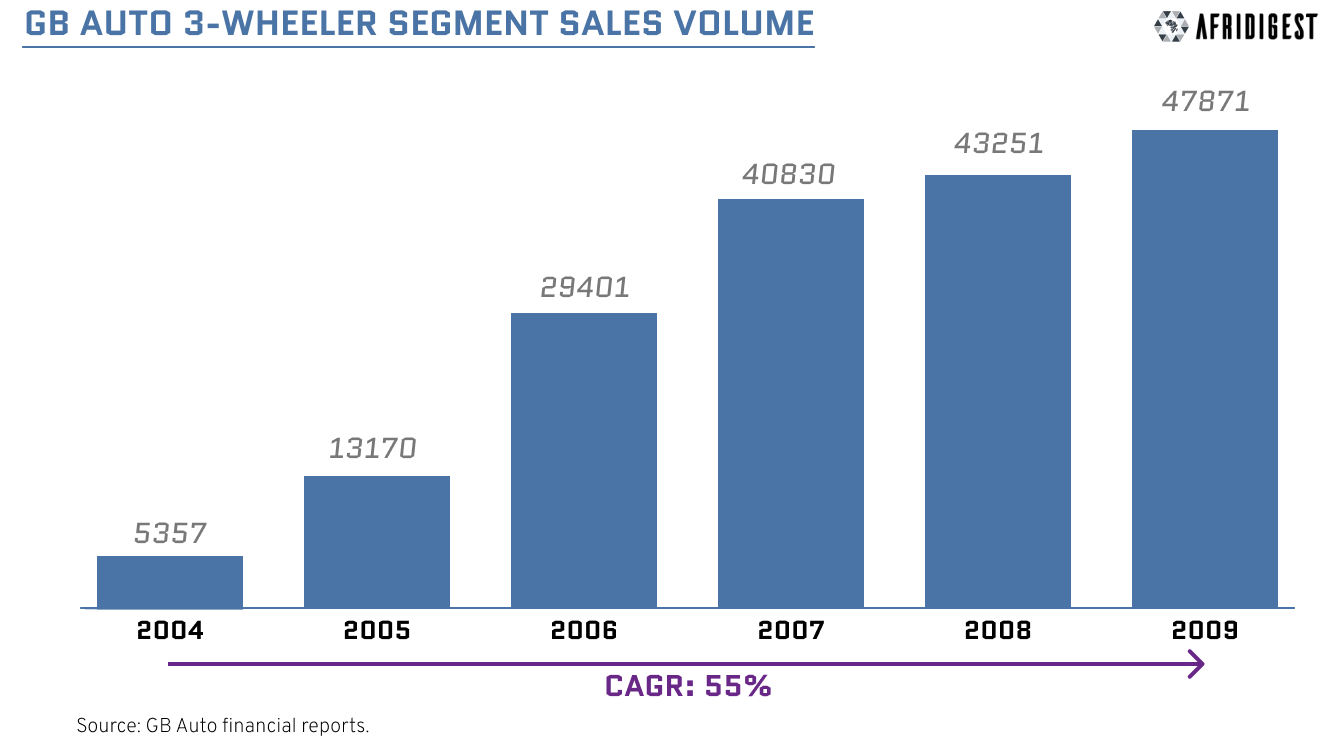

And by then, EGX-listed Ghabbour Auto (GB Auto), a leading player in the MENA region’s automotive sector, was at the helm with a 90+% share of the country’s fast-growing tuk-tuk market.

As the exclusive assembler and distributor of Bajaj, the most popular tuk-tuk brand in Egypt, GB Auto was well-positioned to capitalize on this new opportunity.

But there was one main obstacle: the lack of financing in the country.

Tuk-tuk operators were largely seen as irresponsible at the time, and commercial lenders across Egypt generally avoided the sector.

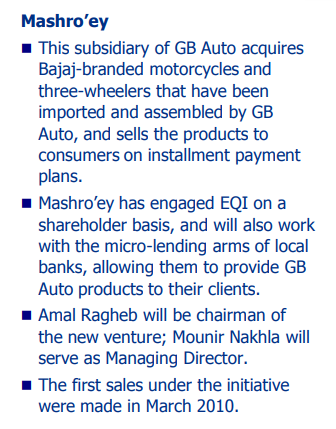

But GB Auto was confident that credit would unlock significant consumer demand for tuk-tuks, so it took direct action. It approached EQI and Nakhla about forming an asset financing joint venture to be called Mashro’ey (“my project” in Arabic).

Nakhla was in.

Sensing a lack of competition and the opportunity to address an underserved market, he co-founded Mashroey as a GB Auto subsidiary in 2009, serving as its Managing Director.

And because the project would rely upon GB Auto’s network of dealers, distributorships, and lending partners, ownership of Mashroey was split 90% in GB Auto’s favor, with EQI owning 10%.

Source: Q1 2010 Investor Presentation (PDF). GB Auto

It was an overnight success.

Just three months after launching operations, Mashroey was driving over 10% of sales for GB Auto’s motorcycles and three-wheelers segment, while reporting almost no defaults.

GB Auto noted in its 2010 annual report:

Mashroey remained an important sales driver for GB Auto over the next five years, riding a wave that saw close to a million tuk-tuk taxis in Egypt by 2015. And it was proof that providing financial services to unbanked & underbanked segments made sense not only socially, but commercially too.

Nakhla told UAE’s The National in 2010: “I had general managers of banks calling me up and telling me, ‘Mounir, you’re going to lose a lot of money [lending to tuk-tuk drivers]. These are all criminals.’ But I find them to all be honest men. They’re just normal people. This stigma, this stereotype, is very unfair.”

The Tasaheel opportunity

In June 2015, given the success of Mashroey, Nakhla founded a new microfinance venture, Tasaheel, that leveraged GB Auto’s existing capabilities. It was again incorporated as a GB Auto subsidiary 90% owned by the firm and 10% owned by EQI.

Targeting a new underserved Egyptian segment, women, it offered short-term group lending to female micro-entrepreneurs.

Nakhla said at the time:

Two years later, by the end of 2017, the company was well ahead of its five-year target. It had over 100 operational branches, served ~250,000 customers, and employed over 2,500 people.

And today, as you read this, Tasaheel is the largest microfinance company in Egypt.

Source: 2017 Annual Report (PDF). GB (Ghabbour) Auto.

The making of MNT (Mashroey and Tasaheel)

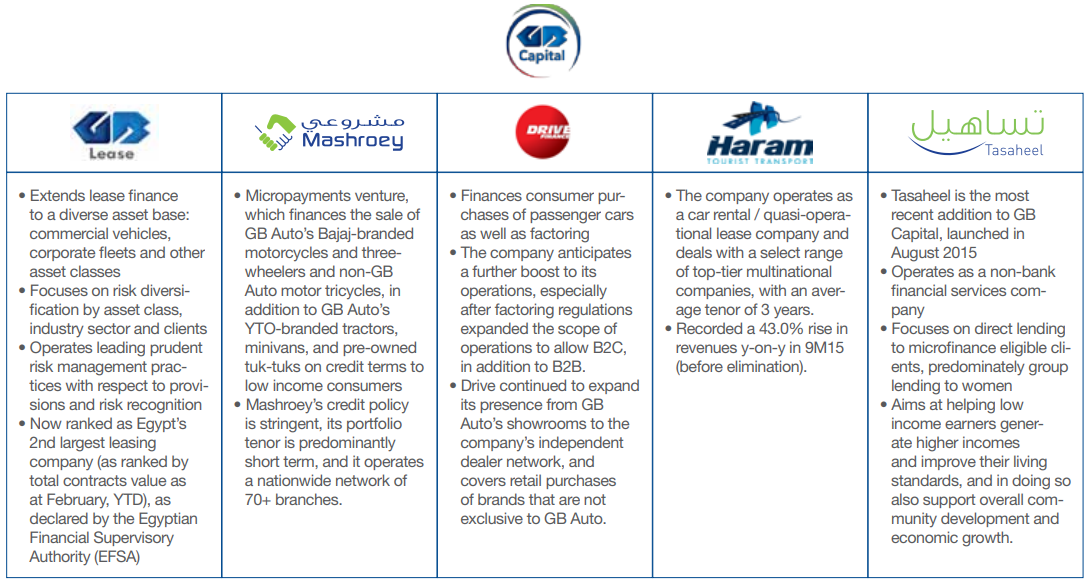

By the end of 2018, Mashroey and Tasaheel were not only the fastest-growing units in GB Auto’s high-margin financing business (GB Capital), they also generated 40% of its revenue, jointly taking in over 2 billion Egyptian pounds (roughly $116 million at 2018 exchange rates).

GB Capital business units. Source: GB Auto Investor Presentation FY 2015.

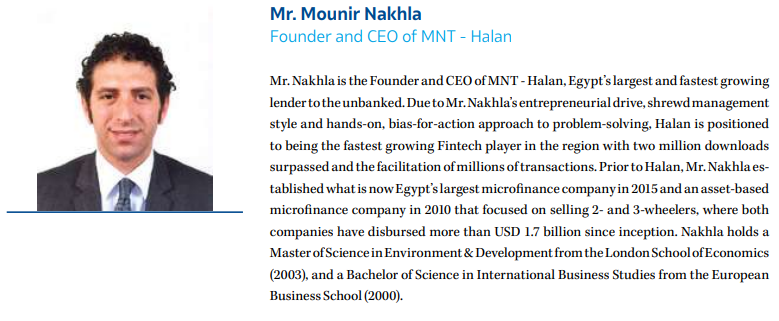

With an eye toward unlocking value for shareholders, GB Auto bundled the two firms together in 2018. It formed MNT Investment as a holding company for Mashroey and Tasaheel under the stewardship of Nakhla who would serve as the new company’s Founder, Chairman, and CEO.

GB Auto transferred 75% of its stake in both companies to the new holdco, while holding its remaining stake directly (via GB Capital).

And later in 2018, it coordinated the sale of a 33% stake in MNT Investment to private equity firm Development Partners International (DPI) for $45 million, valuing the new holding company at ~$135 million.

The Halan proposal

The year before MNT Investment was officially formed, however, Nakhla was approached during a trip to Asia by veteran emerging markets fund manager David Halpert.

In a 2017 meeting that was reminiscent of GB Auto’s approach eight years earlier, Halpert made a proposal to Nakhla: given his experience within Egypt’s mobility and microfinance sectors, why not build out a super app for the region?

While Nakhla’s success with Mashroey and Tasaheel was undeniable, Halpert suggested that he could create more value and impact by infusing technology into his efforts.

And having previously invested in Bangladesh’s Pathao, India’s Rapido, and Indonesia’s Gojek via Battery Road Digital, Halpert was well-connected within the sector and secured a meeting for Nakhla with Gojek’s Founder & CEO Nadiem Makarim.

Nakhla was in. Again.

He recognized the opportunity to leverage technology to achieve greater scale and impact. So, he co-founded Halan in April 2017 alongside serial entrepreneur Ahmed Mohsen to “be the app of underserved communities,” as he told CNN.

After raising over half a million dollars from Battery Road, GB Auto’s CEO Raouf Ghabbour, and Nakhla himself, Halan officially launched in November 2017 as the first mobility app in Egypt to focus on motorcycles and tuk-tuks.

The app initially offered just ride-hailing services but expanded five months later to include food delivery and on-demand courier/logistics services shortly afterward.

Mounir Nakhla in the backseat of a Halan tuk-tuk taxi. Source: CNN.

But while the team focused on growing Halan’s transport offerings, Nakhla saw mobility primarily as a means to an end; he saw it as a catalyst for rapid growth and efficient customer acquisition.

He told Entrepreneur Middle East in 2019:

One year after its launch, Halan had completed over 3 million trips and announced a ~$4.3M Series A co-led by Battery Road and Algebra Ventures.

And by the end of Q1 2019, it had completed over 10 million rides and deliveries, crossed the milestone of 1 million app downloads, and had over 100,000 customers.

By September 2019, Halan was completing “a few million rides per month,” according to Nakhla.

By most external measures it was a success.

But despite the company’s significant top-line growth, Nakhla had profitability on his mind.

And the examples of Lyft and Uber only helped to bolster his thinking. Both ride-hailing platforms had gone public earlier in 2019 but were trading 25-40% down from their IPO prices as investors questioned their unit economics.

Nakhla assessed the reality of Halan objectively.

So he and Mohsen decided to change tack. They reduced the company’s investment in ride-hailing and delivery and refocused the team on financial services with Mashroey and Tasaheel in mind.

Halan was no longer a ride-hailing business, it was to become a platform offering digital financial services to Egyptians, underpinned by proprietary software.

MNT-Halan: The fintech ecosystem

As Halan ramped up its focus on financial services, launching new BNPL, microfinance, and payments solutions, GB Auto was also taking action as MNT Investment’s majority shareholder.

In April 2021, it sold a 5% (indirect) stake in MNT Investment at an implied valuation of ~$450M (at 2021 exchange rates). Then it acquired Raseedy, the first independent and interoperable digital wallet licensed by the Central Bank of Egypt.

And in June 2021, MNT-Halan was born.

MNT Investment officially acquired Halan, creating the MNT-Halan entity in a share swap transaction that brought together lending units Mashroey and Tasaheel, digital wallet Raseedy, and Halan, the former ride-hailing platform turned lending, payments, and e-commerce provider.

Source: GB Auto financial reports.

Months later in September 2021, MNT-Halan announced raising $120 million in a round led by Development Partners International, Apis, and Lorax Capital Partners.

And the company’s new identity was clear. It began describing itself as a ‘fintech ecosystem’ rather than a super app and as ‘Egypt’s largest non-bank lender to the unbanked.’

Source: Q4 2021 Investor presentation. GB Auto.

According to GB Auto financial disclosures, MNT-Halan generated ~$255 million in revenue in 2021 (at 2021 exchange rates), up 30% y/y from the ~$196 million it generated in 2020.

Source: 2021 Annual Report (PDF). GB Auto. Note that the Egyptian pound (Livre Égyptienne) has since weakened.

And the company no longer offers ride-hailing. The vast majority of the revenue MNT-Halan generates today comes from lending of various types — vehicle financing, microfinance, business lending, BNPL, payroll lending, & more — and an increasing amount is generated directly from its consumer-facing app, Halan.

At the same time, the company continues to build out an ecosystem of digital financial services including e-commerce, payments, and more, that supports its lending efforts.

In June 2022, for example, it acquired Egyptian B2B inventory restocking e-commerce platform Talabeyah, bringing new merchants and vendors needing credit onto its platform and “increas[ing] the stickiness [of] its ecosystem.”

And while MNT-Halan seems to no longer position itself publicly as a ‘super app,’ it’s still guided by the super app model.

From a business point of view you want to engage the customer on multiple fronts through one interface and provide multiple services…

We started off [as] Halan [doing] ride-hailing for two and three wheelers [then] we combined with MNT and we created probably the largest fintech play in the region, where we’re banking the unbanked through one interface.

Financial services, although [they] have fantastic unit economics, don’t have a lot of engagement so this is where the super app [playbook] comes in — you add on multiple services to engage the customer and be able to have multiple touch points with different profiles of customers, and that’s what we’re doing now.Mounir Nakhla, Nov. 2022

Africa’s newest unicorn

In October 2022, GB Auto disclosed that MNT signed a definitive agreement “for the sale of a 21.7% stake” to UAE-based investment firm Chimera at an implied minimum valuation of $800 million (up to $950 million with earnouts).

And a few weeks ago, according to MNT-Halan’s press release and Apis disclosures, Chimera acquired “over 20%” (presumably 21.7%) of MNT-Halan for “more than $200 million,” all (or the vast majority) of which was in secondary sales from existing investors.

The company is currently in talks with the IFC and other investors to raise another $60 million in primary capital, after which “MNT-Halan’s valuation will exceed $1 billion.”

Today, MNT-Halan has 1.3 million monthly active users, serves more than 5 million customers in Egypt (2 million of which are borrowers), and takes pride in having “the largest tech team in the region,” with over 120 engineers.

And it says it generated over $300 million in revenue in 2022.

What’s next for the firm?

“My life has always been [about] targeting underserved communities.” — Mounir Nakhla

Two hundred years before Alexander the Great’s visit, Persia’s King Cambyses II reportedly sent 50,000 soldiers to destroy the temple of Amun Ra at Siwa.

And according to Greek historian Herodotus, the men were swallowed up by the desert and the entire army was lost before arriving.

Alexander the Great, according to legend, avoided this fate thanks to divine aid — he was said to be guided through Egypt’s unforgiving Western Desert by two ravens.

Mounir Nakhla had ravens of his own in building MNT-Halan into what it is today. David Halpert, for example, sparked the idea of focusing on tech. And publicly-traded firm GB Auto lent its heft to his various efforts.

While it’s perhaps not widely known or appreciated, many of Africa’s unicorns and soonicorns have enjoyed similar support from larger organizations, at least in gaining an initial foothold. Strong parallels exist with Access Bank’s initial support of Flutterwave, Interswitch’s bank consortium approach, Opera’s backing of OPay, Transsion’s pre-install support of PalmPay, and more.

Those collaborations, although sometimes glossed over or shushed, are important to note for those seeking to create and support valuable companies. And they don’t diminish the efforts and industriousness of innovators building the future across the continent.

“Nature hath placed nothing so high that it is out of the reach of industry and valor.” — Alexander the Great

If you liked this, subscribe to the newsletter.

Share: