Last-mile distribution—delivering products and services to end customers—continues to be one of the biggest challenges that firms offering digital services face in achieving scale across African markets.

Among other factors, infrastructure is generally underdeveloped, connectivity isn’t yet widespread, and education and literacy levels can be low.

For example, according to the World Bank’s most recent figures, just 30% of the population in sub-Saharan Africa uses the internet, and there are just 7 ATMs and 5 bank branches for every 100,000 adults in sub-Saharan Africa (compared to 88%, 214, and 25, respectively, for North America).

Necessity is the mother of invention, however, and it’s against this backdrop that agent networks developed to become crucial links between end customers and the various actors trying to reach them, from dense urban areas to remote rural regions.

Agents are generally third-party micro-entrepreneurs incentivized to conduct certain transactions on behalf of service providers (e.g., telecommunications companies). And, in the abstract, agents & agent networks can be:

- Proprietary or non-proprietary — developed and managed directly by service providers themselves or owned and managed by external parties

- Exclusive or non-exclusive — serving only one provider or serving multiple providers at once

- Dedicated or non-dedicated — conducting agent business on behalf of service providers alone or conduct other kinds of business (e.g., retail) in addition to the agent business

- Static or mobile — linked to a physical location (e.g., retail outlet or kiosk, gas station, post office, etc.) or on the move and able to meet customers in convenient locations

DFS agent networks

Thanks in large part to M-Pesa’s success with the agent model, agent networks dominate the provision of digital financial services (DFS) across the continent today. They enable, for example, individuals in cities to convert physical cash to mobile money and send it to relatives in rural areas who then withdraw it as cash.

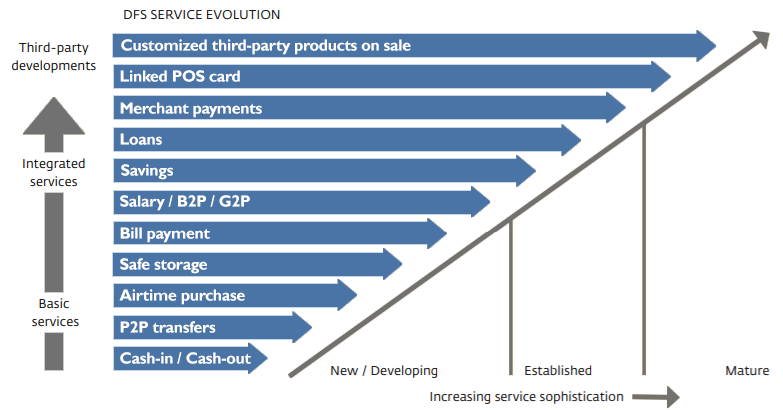

On a continent where up to 90% of retail transactions are still cash-based, cash-in and cash-out (CICO) has historically been the dominant function of DFS agent networks whether led by MNOs like Safaricom, by banks, or by various fintech providers.

But increasingly as trust & familiarity grow, not only are DFS agent networks getting more sophisticated (e.g., M-Shwari offering savings & micro-loans), but new players are leveraging the agent network model beyond traditional digital financial services.

Select DFS agent network players

- Telcos: Safaricom, MTN, Airtel, Tigo

- Banks: Ecobank, FirstBank Nigeria

- Fintechs: Fawry, OPay, Paga, TeamApt, Nomba, Wave, Bankly

E-commerce agent networks

Once regarded primarily as a key driver of financial inclusion, agent networks are increasingly being leveraged to amplify e-commerce activity across the continent.

Because of pre-existing trust and social capital within their communities, agents can be unusually effective at customer acquisition, education, and engagement, and various e-commerce platforms have taken note.

In Egypt for example, Brimore is building a business underpinned by the agent network model — it offers a direct-selling platform that helps local manufacturers and SMEs sell their products directly to consumers through a proprietary network of over 75,000 sales agents, the vast majority of whom are women. The company raised a $25 million Series A earlier this year.

In Kenya, Copia, a mobile commerce platform, operates a network of over 25,000 agents who earn commissions by aggregating orders and serving as pick-up points for “remote, unbanked, [and] unconnected” customers in rural areas of Central Kenya.

To date, Copia has completed millions of orders with returns as low as 4% of the GMV of delivered items. The company has raised over $100M in total funding, including a $50 million Series C earlier this year.

Elsewhere on the continent, ride-hailing startup SafeBoda is no stranger to the agent model. Since 2019 in Uganda, the company has enabled its drivers to act as DFS cash-in agents that convert physical cash collected from users to SafeBoda wallet credit.

And it’s not just cash-in, the company also announced a partnership with energy major Total to facilitate agent-driven commerce: the cashless purchase of fuel via SafeBoda agents.

1/3 At Total fuel station, find a SafeBoda Agent, inform that you wish to purchase fuel through the SafeBoda Wallet for the #SafeBodaxTotal discount. pic.twitter.com/XVcQigoRbJ

— SafeCAR | #NoTuteeseOffline (@SafeBoda) August 11, 2021

The largest and most well-known e-commerce agent network across Africa is likely Jumia’s, however. At the time of its 2019 IPO, the company asserted that it had ~40,000 sales agents across the continent; these agents place orders on behalf of end customers and earn commissions for each item successfully delivered.

Other agent networks

While DFS and e-commerce are proving to be among the strongest use cases for agent networks across African markets so far, the agent network model is being deployed successfully to drive results for other digital players as well.

For example, across its African markets (Egypt, Ghana, Ivory Coast, Kenya, Nigeria, South Africa, Tanzania, and Uganda), Uber offers the Uber Hero program — an agent network that incentivizes third parties to sign up new drivers and earn commissions when drivers become active.

Similarly, before shifting its focus to Western markets, Nollywood-focused subscription video-on-demand platform IrokoTV employed the agent network model both for customer acquisition and for distribution — agents earned commissions for every subscription sold and for every movie sent to customers via WiFi Direct technology.

Notably, however, agent networks aren’t only applicable to commercial contexts, they’ve also proven valuable in the provision of public services. Rwanda’s Irembo, for example, is a government portal launched in 2015 that offers services like birth & marriage certificates, driver’s license registration, land transfer, and visa applications to Rwandans; in order to broaden its reach across the country and ensure widespread accessibility, it uses a network of over 4,000 agents who earn commissions by facilitating various transactions.

Agent network aggregators and infrastructure providers

As agent networks increasingly spread across various verticals and use cases, the opportunity for value creation via aggregation and the provision of underlying infrastructure increases as well. It’s not surprising then that agent-networks-as-a-service (ANaaS) offerings are on the rise.

In Kenya, Tanda, for example, aggregates all major DFS agent offers in the country into a single platform, allowing agents to earn commissions conveniently, regardless of the provider preferred by the end customer. The startup also addresses a key issue faced by DFS agents—liquidity and float management—by extending credit to its agent-users.

PesaKit, also from Kenya, does much of the same — aggregating providers into a single platform and offering float loans & micro-insurance; it currently serves over 7,600 DFS agents and uses predictive analytics to offer its agent-users relevant & timely business insights.

While ANaaS players focus on aggregation, others focus on more basic agent network infrastructure. Waynbo, Opareta, and Upya Tech, among others, build software tools to help providers deploy, manage, and measure proprietary agent networks. And companies like Optimetriks help DFS providers map and audit their agent networks.

Agent networks: not just for mobile money

While agent networks have been long heralded as the underlying foundation of Africa’s thriving mobile money economy, less appreciated is their increasing influence across a variety of sectors.

The reality is, however, that given current dynamics across African markets, the agent network model is particularly well-suited to drive scale & business impact as a last-mile channel for acquiring, educating, and engaging end customers.

Moreover, as ‘agent networks for X’ become more widespread, there will be a diversity of opportunities for innovators to create & capture value across the agent network ecosystem.

Interested in going deeper? Our affiliate company Africreate supports startups, corporates, and investors with strategic intelligence on the intricacies of innovation across African markets and how to best capture relevant opportunities.

Share: