Editor’s note: This is a two-part contribution from Chris Maclay, Program Director of the Jobtech Alliance at Mercy Corps.

This first part calls attention to the crisis of missing jobs across Africa, and highlights the role jobtech plays in the continent’s labor markets. A second part will explore the opportunities for jobtech platforms in Africa in 2024.

As discussed in ‘The hierarchy of venture opportunities in emerging markets,’ ventures that enable entrepreneurship & economic empowerment are among those best-positioned to succeed in African markets right now, and, as such, it’s worth keeping an eye on the jobtech sector.

African countries will add more people to the global workforce in the next 10 years than the rest of the world combined. But there aren’t enough jobs for these young people.

An average of 9 million jobs have been added to African economies annually since 2000, but 20+ million young Africans will reach working age each year for the next two decades. Fundamentally, we aren’t yet creating enough jobs to sustain Africa’s growing youth population.

To be clear: Not only does the current pace of job creation have to be maintained, 10+ million more jobs need to be created each year over the next two decades just to keep up with the number of young people entering the labor market. That’s right, we need a 2x increase in jobs created, just to keep the current levels of unemployment.

But not only have we failed to create loads more jobs in Africa over the last few years, economic stagnation has led to layoffs in the few sectors that were actually providing jobs. We talk a lot about reducing unemployment in Africa, but it might require a small miracle for unemployment not to substantially increase over the next decade.

As Louise Fox and the Africa Growth Initiative team at the Brookings Institution rightfully declared, “Africa’s ‘youth employment crisis’ is actually a ‘missing jobs crisis’.”

The crisis isn’t an inherently African problem, however. It’s really a timing issue.

African populations are booming at a time when that the role of labor — particularly lower-skilled or mass-market labor — is shrinking. A dilemma for African economies is that labor fundamentally doesn’t seem to be as ‘required’ as it used to be.

So where will jobs come from and where should we focus our efforts?

At the Jobtech Alliance, we believe that jobtech platforms will play an increasingly important role in African labor markets over the next decade. Indeed, they already do.

Jobtech platforms (digital platforms that enable, facilitate, or improve users’ ability to access and deliver quality work) can not only play a big role by improving efficiencies in the labor market, but also by stimulating demand and truly creating employment.

What really is employment in Africa? What role does jobtech play?

Let’s start by examining what employment really is in African markets.

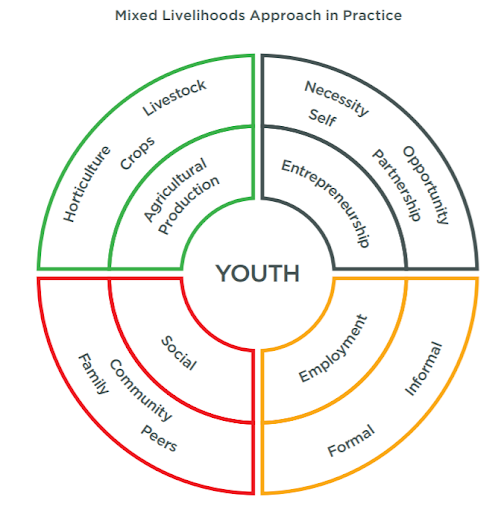

Rather than a binary condition of being employed or unemployed, most young people in Africa today earn their living through a ‘mixed livelihood’ or ‘portfolio of work’ approach, which includes a combination of informal and formal wage labor, self-employment, agricultural, and/or unpaid family work.

Source: Mastercard Foundation

Mixed livelihoods for young Africans don’t look like jobs in the traditional sense. For example, young people in East Africa simultaneously engage in approximately three income-generating activities on average.

With young people juggling multiple income streams at once and constantly looking for new earning opportunities, digital platforms have the potential to play a significant role in increasing access to work, learning, and business opportunities.

These include job matching platforms (e.g., Jobberman, Brighter Monday, Fuzu), gig matching platforms (e.g, Uber, Upwork), and platforms that digitize entrepreneurship (e.g., e-commerce marketplaces like Jumia & platforms like Wasoko that digitize backend operations).

The world of jobtech — which we define as the use of technology to enable, facilitate, or improve people’s ability to access and deliver quality work — is broad. Our full taxonomy of the sector is available here.

To put it simply, jobtech is the future of work in Africa.

Other than the advent of AI and remote work, no other innovations outside of jobtech platforms have had a bigger impact on European and North American labor markets over the last few decades. In Africa, their role will be different, but we can certainly expect them to have a significant impact.

30-88 million Africans will earn from jobtech by 2030 according to estimates from research-led innovation firm BFA Global. And data from business intelligence platform Briter counts over 750 jobtech platforms in Africa today. That number is only going to grow over the next decade.

Is jobtech the solution to youth unemployment in Africa?

Unfortunately, the macro conditions outlined above don’t make for a highly conducive environment in which to build jobtech platforms.

These platforms are fundamentally about connecting labor demand to supply, so economic contractions generally lead to a reduction in demand. From a start-up perspective, you might call this a case of a frustratingly small total addressable market (TAM) — and that TAM has been shrinking over the last year.

Even without a demand crisis, building jobtech platforms in Africa is operationally challenging on the supply-side. At its simplest, it still involves solving multiple, layered development challenges.

Contrast that with TaskRabbit in the US, for example. The San Francisco-headquartered marketplace for freelance labor works within a broadly functioning labor market. It can tap into a large supply of skilled and accredited plumbers who are able to travel to clients, buy quality materials, and maintain customer relationships.

The equivalent platform in many African markets has to manage, among other issues, low levels of vocational training and lack of functionally usable accreditation, a lack of tools and equipment, minimal working capital and few financing options, a broken supply chain of quality materials, unreliable and expensive public transport to get to gigs, communication gaps between workers and clients, weak trust in platforms, high levels of platform disintermediation, and the list goes on.

Theoretically, all the issued mentioned above could be solved or mitigated, at least within specific verticals. (See for example, our experiences building Kenyan home services platform Lynk.) However doing so comes at a cost, and customers, many of whom are extremely price sensitive, are often unwilling to bear it.

| Demand | Platform | Supply |

| • Lack of local demand for labor • Mass market is highly price-sensitive consumer (will often not pay more for quality) • Often analog preferences, disintermediation |

• Weak technical skills • Weak soft skills • Lack of tools, equipment, PPE (and financing) • Often inadequate infrastructure (affordable transport, affordable internet) • Often analog preferences, disintermediation |

This is why traditional matching marketplaces have struggled to really hit scale in most of Africa.

While basic marketplaces solve for information asymmetry (i.e. ‘How do I find the best provider of goods or services at the right price?’), the provision of information alone in most African markets simply does not solve enough of what’s often a broken system.

There are exceptions of course. In Ethiopia, for example, we’ve seen some matching platforms rapidly scale as they’ve created access to information about talent for the first time.

But in general, jobtech platforms in Africa need to innovate around supply, demand, or both to be successful. Given the crisis of missing jobs in Africa, innovating around demand offers the most leverage today, and that’s where the opportunity for jobtech platforms lies in 2024.

I explore those opportunities in the second part of this essay. Stay tuned.

Share: